![]() After being blacklisted by Japan’s movie studios in 1967 for—as he himself put it later—making “films that make no sense and make no money,” nonconformist director Suzuki Seijun spent a decade confined to making television and video projects before being allowed to helm another feature. His comeback movie, 1977’s A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness, proved every bit as strange and singular as the films that got him shut out of studios in the first place.

After being blacklisted by Japan’s movie studios in 1967 for—as he himself put it later—making “films that make no sense and make no money,” nonconformist director Suzuki Seijun spent a decade confined to making television and video projects before being allowed to helm another feature. His comeback movie, 1977’s A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness, proved every bit as strange and singular as the films that got him shut out of studios in the first place.

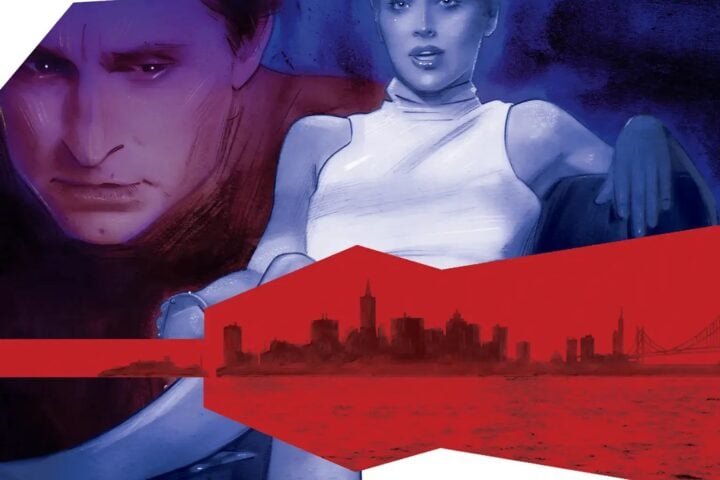

Opening as a spoof on the magazine industry, the film initially focuses on a golf publication cooking up a PR stunt to train a young fashion model, Reiko (Shiraki Yoko), to play the sport just well enough to enter a tournament. To the shock of everyone, she proves to be a natural. She’s such a savant that she suggests a classical oracle, fainting in a kind of ecstasy with each perfect swing.

Emerging victorious from the tournament, Reiko becomes a massive star, and the magazine and various sponsors immediately map out a media saturation campaign that sees her elevated to the life of luxury but also makes her the target of an obsessive fan, Senboh (Enami Kyko). When Reiko and her manager, Miyake (Harada Yoshio), accidentally clip the woman one night while speeding in her sports car, Senboh blackmails the star into making her a confidant.

Senboh’s entrance into the film shifts the story from a commercialization satire closer in spirit to Masumura Yasuzo’s Giants and Toys to a darker psychological thriller. At this point, Suzuki lets his maverick aesthetic sense take over to visualize the depths of Senboh’s fame-worshipping madness and the way that it manifests as a desire to control the object of her affection.

A shot of Senboh inside Reiko’s home sees the model in the right of frame, standing on the overlit practice green built into her mansion as if she were posing for a photoshoot. Meanwhile, Senboh sits in the left of the frame cloaked in shadow, the room almost perfectly bifurcated between the extremes of light. It’s a brilliant Mephistophelian demonstration of the stalker’s evil. Later, after Senboh has installed herself in the house as a permanent guest, she sits down for breakfast with her dull and obedient husband (Koike Asao) in a scene that initially scans as a vision of contented domesticity—until the camera tilts down to see the woman’s reflection in a glass table that tints her skin a necrotic green, as if revealing the monster within.

As Senboh takes up more and more space in Reiko’s life, she becomes increasingly drunk with power, leading to absurdist scenes like one in which she invites a throng of other Reiko obsessives to the star’s home and presides over a grotesque fashion catwalk with the practice green as a makeshift runway. For her part, Reiko clearly submits to these humiliations because they’re consistent with the ways that Miyake and sponsors exploit her. Perhaps the most disturbing suggestion, though, is the degree to which Senboh and other fans become victims of their own obsession, both wardens of the cage in which they place the model and fellow prisoners incapable of escaping their own deluded fantasies.

All of Suzuki’s long-established aesthetic trademarks are present in the film: the strange and surreal visual compositions, the disorienting editing that borders on free association, the bold use of color. But he modulates them away from the anarchic frenzy of his ’60s work and toward a more outwardly stately tone that ultimately makes his idiosyncrasies all the more odd and unnerving. The director would develop this method even further throughout his Taisho trilogy in the ’80s, his most commercially successful works and triumphs of a mature style that sublimated his youthful anarchy into a more multifaceted, carefully modulated approach.

Image/Sound

Radiance’s transfer comes from a high-definition scan of the film’s negative provided by Shochiku that sports more than a few instances of wear and tear. Small scratches and spots recur throughout the film, and grain can be uneven and overly thick at times. Nonetheless, the rich greens, yellows, and reds of the cinematography pop in all their intensity, while the expressionistic fluctuations in lighting never result in a hazy or softened image. The soundtrack consists of little more than dialogue and the occasional intrusions of the music score, and these elements are well balanced to keep the former consistently clear.

Extras

On his new commentary track, critic Samm Deighan discusses Suzuki Seijun’s career and time away from studio filmmaking, as well as aesthetic and thematic through lines that connect A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness to the ones that Suzuki made before and after. The disc also includes a new interview with editor Ukai Kunihiko in which he details the director’s unorthodox method of assembling the film, treating each scene as its own self-contained short movie as opposed to focusing on the overall flow of the cut. A booklet contains an archival interview with screenwriter Yamatoya Atsushi and an essay by critic/filmmaker Jasper Sharp that covers the film’s place in Suzuki’s career and those of some of the director’s collaborators.

Overall

Suzuki Seijun’s comeback film is a key moment in the maverick director’s career, and Radiance’s disc offers a welcome chance to evaluate its subtle ingenuity.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.