![]() As expansive and iconic as its title suggests, Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West certainly seemed to be written in John Ford’s blood, from the vast wide-angle visions of Monument Valley that Leone and cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli luxuriated in, to the railroad-based, future-of-America economic landscape that serves as a backdrop to a number of bandit-versus-bandit power plays. Henry Fonda, with that methodical, stately stroll of his and those killer blue eyes barely visible from under the rim of his hat, can be seen and heard throughout, sending a shiver of great nostalgia up one’s spine. Ripened and tanned by years of desert sunlight, Ford’s Wyatt Earp is back in the saddle again.

As expansive and iconic as its title suggests, Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West certainly seemed to be written in John Ford’s blood, from the vast wide-angle visions of Monument Valley that Leone and cinematographer Tonino Delli Colli luxuriated in, to the railroad-based, future-of-America economic landscape that serves as a backdrop to a number of bandit-versus-bandit power plays. Henry Fonda, with that methodical, stately stroll of his and those killer blue eyes barely visible from under the rim of his hat, can be seen and heard throughout, sending a shiver of great nostalgia up one’s spine. Ripened and tanned by years of desert sunlight, Ford’s Wyatt Earp is back in the saddle again.

But that particular pace and posture that Fonda had become known for in such films as My Darling Clementine, matched with the devious glint in those baby blues, now took on a far more sinister tone as we were introduced to his character here, the gleefully sadistic Frank, as he leads the slaughtering of an Irish land owner, McBain (Frank Wolff), and his family. As Frank approaches McBain’s youngest child, just before blowing him away, the hero of so many American westerns seems reminiscent of nothing so much as the Prince of Darkness.

Indeed, Leone’s invocation of the West was as much indebted to directors like Ford, Anthony Mann, and Howard Hawks, as well as such milestones as Delmer Daves’s 3:10 to Yuma and Nicholas Ray’s Johnny Guitar, as the director himself was an agent of epic subversion in the genre that had influenced him and had paid his bills for a sizable chunk of his career.

Fonda’s startling, malevolent turn as the ruthless enforcer for a railroad baron stricken with tuberculosis (Gabriele Ferzetti) was just the tip of the iceberg, as it turned out: Leone’s goal was essentially, like Quentin Tarantino’s with Inglourious Basterds, to form a lacerating critique of the orderliness, selective factuality, and moral cleanliness of genre filmmaking, and from this, the director summoned a western of tremendous power and wild ambition. As the train carrying Charles Bronson’s elusive, solemn gunslinger, nicknamed Harmonica, comes to a halt at a rickety station in the film’s glorious opening salvo, it’s indeed just a train, but it’s also the foreboding phantom of America’s industrialization and “progress,” and the Technicolor resurrection of the train the Lumiere brothers filmed pulling into La Ciotat station.

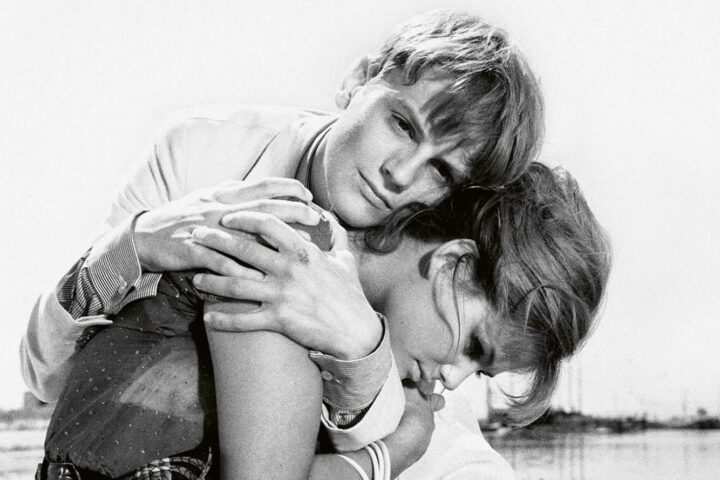

Dreamt up by the director along with future iconoclasts Bernardo Bertolucci and Dario Argento, before being scripted by Leone and Sergio Donati, Once Upon a Time in the West plays out, as the title infers, as a dream image of the cruel Old West, and as such the encroachment of the railroad figures in prominently. Frank’s murder of McBain and his kin would have seemed to put an end to any squabbles over the worth of his land, named Sweetwater, allowing a clear path for Frank’s boss to buy the land, build a small town and make a mint once the railroad inevitably used the land as a station stop. What neither Frank nor his employer could have anticipated is McBain’s marriage to a kind-hearted prostitute, Jill (a fiery Claudia Cardinale), on a trip to New Orleans and her opportune arrival in Sweetwater to claim her place in the McBain family. Instead, she finds herself at the center of a battle of wills and talent between Frank and Harmonica, complicated by a fearsome bandit who befriends Harmonica named Cheyenne, played with incredible charm and just the right notes of menace by the great Jason Robards.

The casting of Bronson, a poster boy for the rising tide of film spectacles in the 1960s like John Sturges’s The Great Escape, against the timeless image of the cowboy Fonda wasn’t the only instance wherein Leone visualized his allegory. The opening sequence involves Harmonica gunning down characters played by Jack Elam and Ford favorite Woody Strode, in roles that replaced Leone’s original idea of having Harmonica kill off the eponymous trio of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. But the casting is hardly the most visual totem of Leone’s almost deadpan subversion, as the advent of color now allowed Leone to call attention to realistic detail.

The station in the film’s opening sequence isn’t the tidy little ticket office that one might remember from a revisionist western such as Sturges’s Bad Day at Black Rock, but a deconstructed shack made of warped planks, dilapidated doorways, and a decaying roof, with a rusted ticker tapping away in the corner. The sight of early construction here isn’t a pretty one, as one can even see the grand imperfection in the construction of McBain’s Sweetwater mansion, calling special attention to the fancy, regal interior design of the railroad baron’s train.

The inclusion of such magnificent visual detail is strongly felt, but the remarkable absences that the film deals in are felt just as strongly, chief among them being the lack of a system of structured law enforcement. The lawmen of so many other westerns are nowhere to be found here, replaced by corruptible guns for hire, vengeance-starved outlaws, and gallows-bound bandits. It’s a further perversion of the generally uncomplicated moral struggles that Ford had championed, allowing for no clear side to root for, especially since the motives of many of these men are left private until the end and are sometimes left a complete mystery, as in the case of Cheyenne. And then, of course, there’s Jill, the symbolic mother and the whore wrapped into a sultry whole and sent out to accomplish nothing less than the building of the new West while the men go off and shoot each other for the dubious cause of “honor.”

It’s to Leone’s credit that such a huge, carefully plotted story isn’t what’s remembered about Once Upon a Time in the West, which is nothing if not the ultimate culmination of the filmmaker’s genre work. What’s remembered is the blue, uncaring sky cast above a dry, ruthless wasteland of a desert with winds kicking up miniscule storms of red dirt, dust, and debris; the way Harmonica moves that harmonica across his parched lips; Jill’s near-ritualistic humiliation at the hands of the cackling, diabolical Frank. The western suddenly became something beyond its incalculable mythology here and mutated into a rapidly evolving and fluctuating state of grim existence, where Ennio Morricone’s typically excellent score holds even sonic weight with the swirling hum of gusting winds in an otherwise silent, barren landscape.

Leone was always a crafter of sounds as well as images, and he isn’t above his more fantastical moments, such as when the sound of crashing waves and singing seagulls accompanies the railroad baron’s obsession with a painting of the ocean, where he hopes to retire to. As it turns out, the railroad baron ends up gasping for air next to a murky, brown puddle of water after Cheyenne’s unseen siege of his beloved train. One can’t help but connect this to the near-universal negative reception Once Upon a Time in the West received from American critics, perhaps scared that the Europeans had reappropriated an intrinsically American genre and had turned a bright-blue painting of an idealist haven into a muddy pool of filth and disease.

Image/Sound

Paramount has taken some flack online for using dual-layered 4K discs for this release, as opposed to the triple-layered discs that Kino Lorber used for its recent spate of Sergio Leone 4K releases. Yet, while this certainly puts a limit on the overall bitrate, there’s little discernible effect on the level of detail in the image, with no signs of visible artifacting.

Indeed, in the film’s extreme close-ups, every crevice, scar, and wrinkle on the faces of Henry Fonda, Charles Bronson, Jason Robards, and others is preserved in microscopic detail. Faces are like maps of the human soul in Leone’s films and Paramount’s transfer captures every last avenue and cul-de-sac. If there’s a fault in the image, it’s that there’s a bit too much grain removal, lending the picture a slicker and slightly more plasticky quality, but, fortunately, it’s not to the extreme degree that there’s any smoothing out the textures of faces or costumes.

On the audio front, the 5.1 surround mix is balanced perfectly to handle both the intricacies of the film’s complex sound design and the grandiosity of Ennio Morricone’s legendary score.

Extras

In a newly recorded audio commentary, Jay Jennings and Tom Betts, hosts of The Spaghetti Westerns Podcast, illuminate fascinating tidbits from the set of the film and touch on the backgrounds of seemingly every actor who walks on screen, from the stars down to the extras. The track is very conversational—perhaps a bit too much at times—but it’s well-researched and the duo’s knowledge of the western genre and its tropes comes through loud and clear.

The second commentary track included here is the same composite one included on Paramount’s 2011 Blu-ray release, featuring such diverse participants as filmmaker John Carpenter, star Claudia Cardinale, and film scholar Sir Christopher Frayling. Despite the fact that there’s an inherent lack of flow to the way the track was put together, a lot of information is pored over. Especially of note are the fascinating takes on Once Upon a Time in the West’s magnificent opening sequence, Leone’s style, and the use of settings.

The three featurettes included on this set also cover similar ground, but they all manage to offer enough fresh opinions and new voices on critical scenes and facets of the production to avoid feeling too redundant. A short featurette on the history of trains in film is interesting, if a bit amateur-looking, as is a short featurette looking at the shooting locations then and now. Rounding out the extras is a production stills gallery and the film’s theatrical trailer.

Overall

While this 4K release is far from perfect, between the additional commentary track and the solid boost in image quality, it’s still a strong upgrade from Paramount’s 2011 Blu-ray.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.