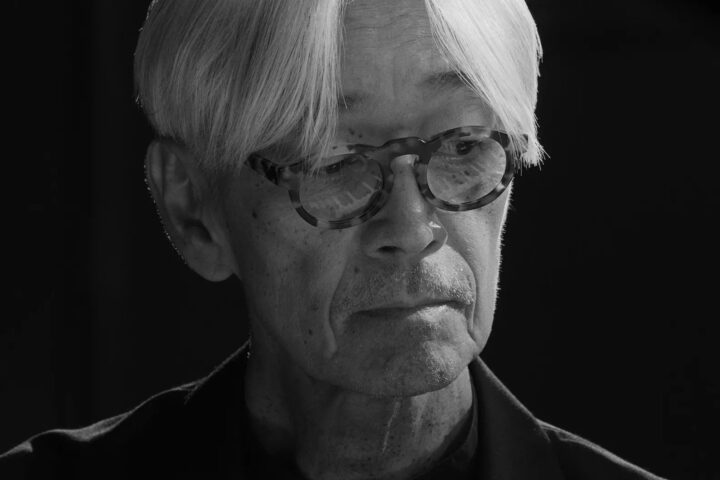

Before Neo Sora’s Happyend introduces any of its characters, the film previews their social conditions. “The systems that define people are crumbling in Japan,” reads a title card at the outset, establishing stakes beyond just the individual circumstances of the characters. While alternately impressive as teen drama and political commentary, the film never satisfactorily synthesizes the two scales at which it analyzes Japanese society.

Happyend’s technological dystopia is a natural outgrowth of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami that destabilized nuclear reactors—not to mention public trust—across Japan. Sora’s film envisions a not-too-distant future where climate change turns the threat of such shocks into an organizing principle of daily life. The country absorbs these constant threats into its security apparatus, which sends out apocalyptic cellphone alerts only to quickly retract its warnings of doom. Predatory enterprises always immediately follow suit, skywriting in the clouds “Emergency Sale: 20% Off Canned Goods” to convert panic into profit.

Happyend finds such odd bits of comedy within the calamity, a feature that helps establish plausibility for the gadget that becomes central to its story. Sora uses a Tokyo high school as a synecdoche for the nation when a principal (Sano Shir) desperate to preserve his power over the subjects in his charge installs a cutting-edge surveillance system across campus. Named Panopty, the cheeky repacking of Foucauldian concepts gamifies the control of the student population. The software operates with a ruthlessly enumerated logic: minus one point for a dress code violation, minus three points for flipping the bird to the camera.

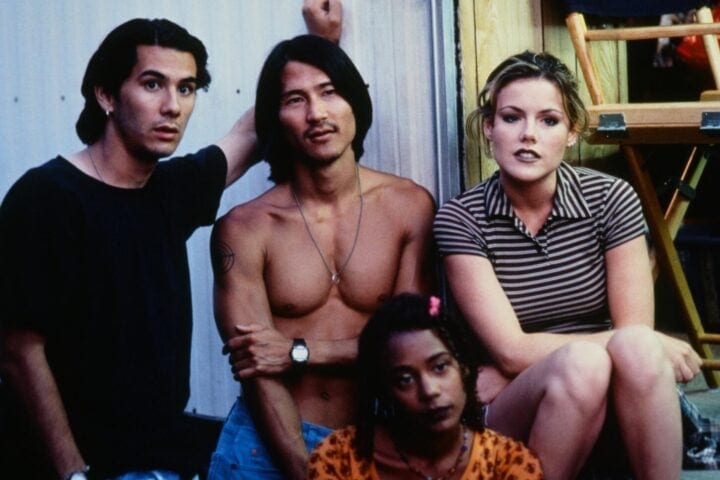

Of course, no demographic group is less likely to submit to mechanized discipline and punishment than teenagers. Happyend captures the periodic fun and perpetual frustration of a crew of miscreants who prompted Panopty’s installation in the first place with a clever prank. Sora unfurls their mischievous maneuver in the key of Steven Soderbergh’s Ocean’s Eleven, even down to the detail of showing how they trick a security guard with phone-derived cat noises. Their rebellious act of flipping their principal’s sports car on its bumper and displaying it like protest art in a courtyard leaves no doubt about their attitudes toward authority.

A familiar struggle between independence and obedience plays out across Happyend, with the emboldened students taking an increasingly militant stance against encroachments on their liberty. It’s a YA plot written by an author who paid attention during sociology seminars. To Sora’s credit, the members of the group feel fully human, not merely stand-ins for teenage archetypes. The dynamic between Yuta (Kurihara Hayao) and Kou (Hidaka Yukito), best friends drifting apart even as their larger circle grows tighter, is the film’s most developed as the effect of radicalizing politics becomes impossible to ignore in their friendship.

Happyend similarly strains to maintain harmony, as its tone wobbles between a more sober social commentary and outright satire. The cartoonish, casual racism spouted by the principal sits awkwardly alongside the more nuanced representation of multicultural heritage in biracial non-Japanese citizen Tomu (Arazi). The axis on which they square off never feels entirely level.

Later, when the students stage a prolonged school sit-in, Sora tips his hand to show sympathy to their youthful idealism as it gives way to fatalism. That proximity to their pain feels constantly at odds with the distancing effect of the film’s near-future surveillance state setting. Sora’s take on the young characters’ activism feels intellectual rather than instinctual, diffusing the charge of the students’ energy. He’s capable of depicting the chaos of their lives, most notably through the turbulence of the sound mix, yet Happyend strains when trying to embody their defiance in a way that might prompt identification from those in the present.

Sora struggles to balance the immediacy of adolescent angst with the long-range outlook of using the students’ experience as a canary in the coal mine for society at large. Further, Happyend never quite satisfies as a microcosmic analysis of Japan because the film never shows enough of the world outside the high school. It’s a confident narrative feature debut, with plenty of insight into the direction of a nation and generation, but it wants for more connective tissue between the small details and Sora’s bigger-picture views.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.