When the helicopters show up in the skies around the nameless Mexican village at the center of Prayers for the Stolen, the safest place to be is in the poppy fields. That’s a perverse irony given the fact that the helicopters are seemingly there to spray the illicit crop with an herbicide as part of a drug crop eradication program.

Instead, a local cartel has paid the operators of the copters to dump the chemicals anywhere else except above the poppies, which means that homes and villagers are often doused in the potentially lethal poison. The poppies, whose bright orange-red flowers dot the lush green mountains around the village, are both the source of the villagers’ troubles and their only means of protection from the viciousness of the cartel, which tends to leave alone those families who participate in harvesting the dark, gummy sap that oozes out of the plant.

That sap will be collected, rendered into heroin, and sold abroad, making a lot of money for some very shady people. Meanwhile, villagers like eight-year-old Ana (Ana Cristina Ordonez Gonzalez) and her mother, Rita (Mayra Batalla), live under the constant threat of violence. In a shot that opens Tatiana Huezo’s film on an appropriately harrowing note, we glimpse Rita and Ana furiously digging a shallow hole, which Ana lays down in. It looks at first like a grave, but we’ll come to understand that it’s the early stages of a hiding place where Ana will sequester herself time and time again, whenever the cartel comes knocking on their door.

Prayers for the Stolen is Huezo’s first fiction feature, to which she brings her documentarian’s eye to the depiction of the story’s milieu, capturing moments that speak to both the scourge of the cartels and the rustic pleasures of lives carved in the rugged terrain of the Sierra Madre. As in Tempestad, Huezo isn’t interested in the gory details of cartel brutality, only what it feels like to live in the shadow of terror. If Tempestad accomplished that with the delicate expressionism of a tone poem, Prayers for the Stolen is more direct but no less subtle.

The film abounds in evocative, granular details about lives gripped by violence. Ana and her friend Paula (Camila Gaal) are forced by their mothers to shear their hair into a boyish crop. By contrast, their other friend, María (Blanca Itzel Pérez), who has a cleft palate, is allowed to keep her flowing locks. The girls are told the haircut is a measure to prevent lice, but it gradually dawns on us that they’re being made to appear undesirable to the unseen men who snatch girls from their homes and force them into horrors that are implied but never specified. María, because of her physical deformity, is seen to be too disfigured to be a worthy victim.

There’s a haunting beauty to Huezo’s depiction of the gradual cross-contamination of childhood innocence and criminal aggression. In one disarming shot, Ana is framed beneath a tightly drawn sheet that glows with a translucent red light coming through her bedroom window, making her seem like a ghost. In this moment, there’s a palpable feeling of anxiety in the air, as if Ana were about to be kidnapped, but it turns out that she’s in the midst of a friendly game of hide and seek. Under Huezo’s quietly expressionistic direction, even such moments of childhood frivolity are enveloped by encroaching danger.

That sense of an omnipresent but largely unseen threat is also conveyed by a rich sound design in which the chirping of birds, the hissing of bugs, and the howling of the wind mingle with the distant sound of gunshots and speeding trucks. In one of the film’s most indelible scenes, Rita and Ana listen to the sounds of the night, trying to identify the moo of a cow and estimating its exact location. This is no mere game but also a kind of survival training.

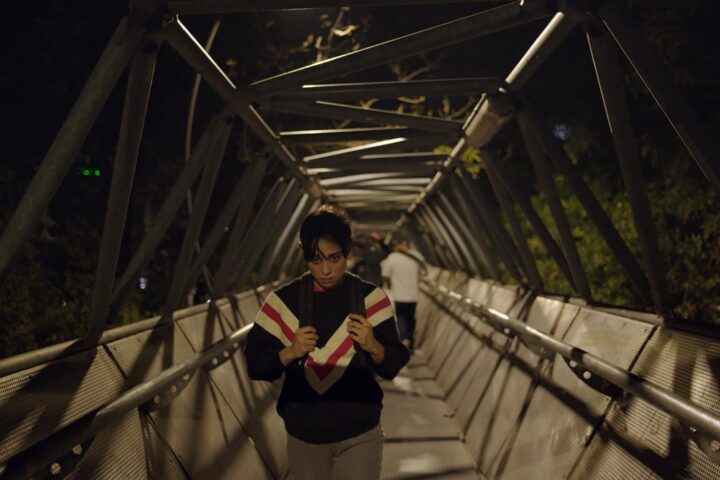

About midway through its runtime, Prayers for the Stolen jumps forward in time and teenaged actors take over the central roles. Ana (Marya Membreo), Paula (Alejandra Camacho), and María (Giselle Barrera Sánchez) are now tweens, and their close-cropped hairdos are no longer enough to play down their femininity. We know that Ana and her pals are now even more likely to be targets of kidnapping, but Ana bristles a bit at her mother’s domineering efforts to keep her safe. Ana harbors a girlish crush on her teacher while engaging in a semi-courtship with María’s brother, Margarito (Julián Guzmán Girón). These scenes between Ana and Margarito at times feel as if they’re injecting unnecessary stakes into an already drama-laden scenario, but at the same time, Huezo manages to vividly link this relationship to her central thematic concern: the gradual encroachment of violence into every aspect of Ana’s life.

The village makes some attempts to organize against their criminal oppressors and take back control of their town, but with the military and police are in bed with the criminals, all efforts at resistance are ultimately doomed. As the film’s original title (Noche del Fuego) indicates, the conflict between the townspeople and the cartel is inevitably heading toward fiery destruction. Like Fernanda Valadez’s similarly themed Identifying Features, Prayers for the Stolen concludes in an inferno, one that destroys any and all semblance of life before these criminal gangs took over vast swathes of Mexico. Perhaps someday people like Ana will be able to look back and reckon with the terror that consumed their youth. But for now, as the film’s mournful conclusion makes clear, there’s little choice but to run.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.