When a woman starts her therapy session by drawing a pistol from her backpack, her new psychologist decides to press ahead with his analysis anyway. That’s the unlikely scenario posed by Max Wolf Friedlich’s Job, the beneficiary of an unlikely Broadway promotion after an extended run last fall at the snug Soho Playhouse on Vandam Street.

The relocation of this two-hander has come with some fancy upgrades: intentionally piercing sound cues, dizzying flashing lights, some extra furniture. But the fancy new digs only accentuate how much of the play is merely padding in the lead-up to a gruesome twist.

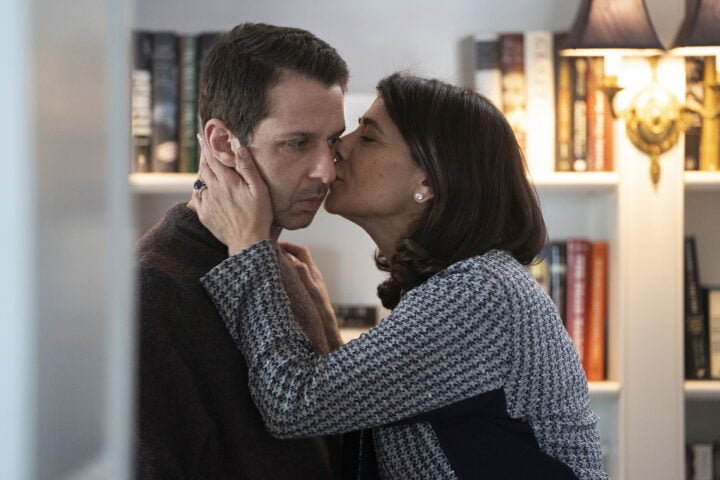

Jane (Sydney Lemmon) recently suffered a breakdown at the tech company where she works, and footage of her shrieking atop a table has gone viral. Before the unnamed Silicon Valley conglomerate will bring her back to the office, she’ll need a thumbs-up from a therapist (Peter Friedman). As the play opens, Jane has just walked into Loyd’s office and immediately pointed a handgun at him. “Next time maybe better for everyone if the gun could stay at home,” he suggests, reasonably, once he’s coaxed Jane into putting the weapon back in her bag.

From there, Loyd evaluates his lively new patient’s fitness for employment while occasionally suggesting they wrap up the session before she tries to shoot him again. Jane is a capable, if apologetic, hostage-taker, though, assuredly disregarding Loyd’s reminder that her 45 minutes are up. Somehow, he never asks her what her job entails (that’s part of the twist, you see), which seems like it might be a good question to lead with before, say, whether she cares that she might be “complicit” in perpetuating gentrification? (That’s part of a tangent, one of many.)

It’s to director Michael Herwitz’s credit that Job preserves an unsettling undercurrent, despite the ridiculous premise, for much of the play’s 80-minute running time. With the exception of jarring lighting and sound effects (including some very discomforting pornographic noises) every time something is said that connects to that all-important twist, Herwitz keeps patient and therapist tensely scrutinizing each other’s every move.

The actors’ specific physical performances almost make the characters plausible. Friedman, best known for his role as Frank on Succession (but particularly beloved by theater fans for originating the role of Tateh in Ragtime), characteristically projects competence and rustic charm. It’s almost believable that Friedman’s self-assured therapist would be just professional and zen enough to continue a session after being held at gunpoint. The man responds to every provocation, even the violent ones, in unshakeable good faith, and only the rare befuddled head quiver or cocked eyebrow suggests the therapist’s skeptical mix of bemusement and terror.

For her part, Lemmon communicates much of Jane’s agitation through posture and movement—anxiously massaging her clavicle, never quite standing straight, constantly hunching over furniture or swaying from side to side. It’s a literally unbalanced performance.

But while Job’s characters may say a lot, it’s not clear that Friedlich has a lot to say. Mental health, the dangerous effects of living online, abortion, the perils of Big Tech, the audacity of whiteness, the aesthetic legacy of the 1960s. Friedlich makes room for all that and more in this theme-hopping therapy session from hell, but Job never takes any of those topics as seriously as it does its own tricksiness. Turns out, the play’s intellectual inquiry, as well as its empathy toward Jane and Loyd, is a red herring. In the end, Job is primarily interested in eliciting gasps of shock from the audience, a cascade of a-ha reactions that arrive in the final minutes.

Jane’s job, when at last unmasked, is a ghastly one. It’s the kind of occupation that makes you think, “Oh, yeah, someone does have to do that, don’t they?” But even understanding where Jane is coming from can’t plug the plot holes that have led her here, nor does Friedlich provide us with time to process the stomach-churning revelations of his play’s disturbing ending.

The play’s climactic pivot from thoughtful interrogation toward shock value finally positions it neither as psychological thriller nor dark comedy, but as horror. In describing, if never depicting, the truly grotesque and evil, Job achieves a sort of tonal homecoming. But its horrors are very real, involving the darkest corners of human behavior. They’re also inexcusably unexplored. Lobbing the bleakest imaginable themes at the audience simply to make the play’s lurid twists pay off makes this hollow play less of a job well done than a piece of work.

Job is now running at the Hayes Theater.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.